What Makes a Shakespearean Scene Great

Conducting an Impossible Experiment in Great Performance

Why Shakespeare is such a big deal

The sheer poetic force of his language

Psychological depth

Many people get caught up in the poetry of Shakespeare, the fearless inventiveness and effortless master of the language. This cannot be underestimated. But that’s not the most powerful thing about Shakespearean drama. In Shakespeare, characters listen to themselves talk and then change as a result. Here’s Harold Bloom from his “Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human”:

“Before Shakespeare, soliloquies tended to be rather formal set pieces in which characters explained themselves to the audience. Shakespeare transformed them into meditations in which characters struggled to understand themselves. When Macbeth or Hamlet talks to himself, we overhear thoughts in the process of formation."

This was certainly a major innovation in the psychological complexity of literature. And, if one accepts Bloom’s thesis, it may very well have been the creation of it. His argument is that Shakespeare “invented human personality” as we understand it today by showing characters who:

Change over time through self-reflection

Exhibit internal contradictions

Overhear themselves think and modify their thoughts accordingly

Develop new aspects of personality through internal dialogue

This is one of those ideas I think about continually. And I am hardly fit to judge whether this audacious claim is true. In fact, I don’t think that this kind of claim is falsifiable in a scientific sense. But it is a very useful thing to think about as a writer. And even if the claim is overstated, there can be no question that Shakespeare opened a vast new territory in the arts and psychology. Do we have depth psychology (Freud, Jung, etc.) without first having deep psychological drama? I don’t think so. And between the seed and the flower lies an incubation period of some 300 years.

A quick look at the difference

Notice how Marlowe lacks any suggestion of “if.” It is all declarative—decisive, unreasoned, all thought through, and laid out neatly. Which, in a sense, is comforting, but it’s not how we are as creatures.

From Marlowe'sTamburlaine the Great:

"Nature, that framed us of four elements

Warring within our breasts for regiment,

Doth teach us all to have aspiring minds:

Our souls, whose faculties can comprehend

The wondrous architecture of the world...

Still climbing after knowledge infinite,

And always moving as the restless spheres,

Wills us to wear ourselves, and never rest."

Compare that with Lady Macbeth. She doesn’t tell us anything. We’re listening to a person’s psyche process guilt. It’s raw, it’s messy, it jumps around… it’s… human.

From Shakespeare’sMacbeth:

"Out, damned spot! Out, I say!—One, two. Why, then, 'tis time to do't.—Hell is murky!—Fie, my lord, fie! A soldier, and afeard?—What need we fear who knows it, when none can call our power to account?—Yet who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?"

What’s in a Performance?

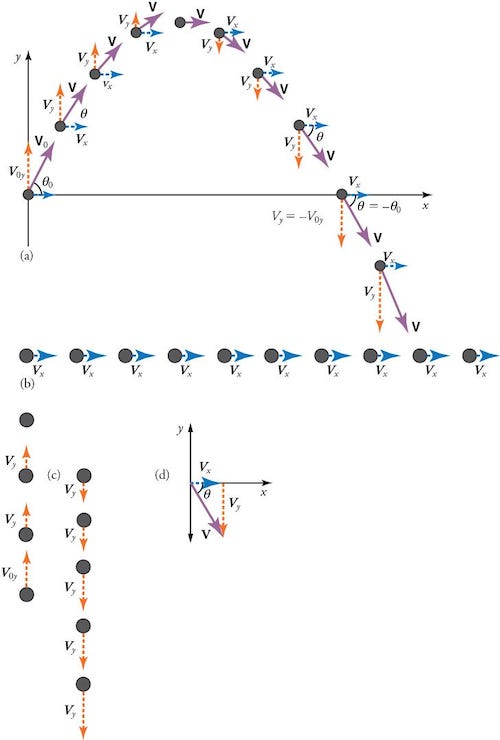

How much of a great scene is the performance? It’s not a question that can be answered because the scene really only exists in the performance. Physics breaks things down into their constituent elements and measures each one. I can take the flight of a cannonball and separate that motion into x and y vectors, demonstrating how the force of gravity works to create parabolic motion over time.

In this simple model, we can see that the horizontal force does not change at all. We can make the model more robust by adding air resistance or a third dimension. But the method remains the same—we can understand a complex phenomenon by breaking it into simpler parts.

This doesn’t really work for stories and scenes. You cannot separate the telling from the tale. What makes Shakespeare a great writer is not the plots he chose, but the way the plots are written. The way the characters convey their interior psychological state in the drama. You can’t really separate the prose from the plot. And you can’t separate the performance from the scene.

It’s why theatre (at its best) is so riveting. It’s just *that* moment—audience and performer going through something together that will never be repeated. When the performance is great, you mourn the fact that the moment can never be recaptured. When it’s bad, you’re immensely grateful you never have to live through it again. But whether it’s lightning in a bottle or a fart in church, it won’t be repeated.

Which makes it impossible to design an experiment to break out the factors in a great scene and measure them separately. Or… is it?

The Impossible Experiment

Take the greatest performers of the last hundred years or so, record them all doing the same scene, and see what’s different. It’s an impossible experiment from a scientific perspective because there’s nothing objective to measure. But I’m not after objective truth here—I’m trying to understand what moves me and how it works. Because I believe that the more I understand that, the more I can move others. And the more I will enjoy all the dramatic art I encounter.

You can run the experiment on yourself because a lot of the greatest actors of the last 100 years have done *Hamlet*. Here are nine of them:

I’m not going to comment on all of them, but I will call out three and highlight what I think are the salient differences:

Branagh is fighting himself—"I’ll be damned if I let you kill me."

Cumberbatch is trying to convince himself—"Please get me out of this mess."

And this one is just great, because it shows the impact of even the smallest choice upon a scene. And good on the King for playing along.

My Favorite Choice

Is Branagh’s. And that’s without liking Branagh very much. He’s a great actor, but something about him always just rubbed me the wrong way. This is probably some strange quirk of my personality because every choice in his “To Be or Not to Be” is serious and brilliant. And it’s my favorite soliloquy because I understand this struggle. I know what it means to struggle with yourself to become better than you are. And so do you. So does everyone. You want to lose weight, but something in you just fights, sweet tooth and sugar claw, to gorge yourself on candy.

The struggle is heightened here because he’s trying to kill himself, but that’s what drama does—it raises the stakes to create emotion. But the fundamental struggle is the same.

Would I give out an award on this basis. Absolutely not. There are many great choices made and yet to be made with this soliloquy. Which, more than anything, illustrates the depth of great works. You can keep coming back to them again and again and find new and deeper meaning. They seem to be inexhaustible.