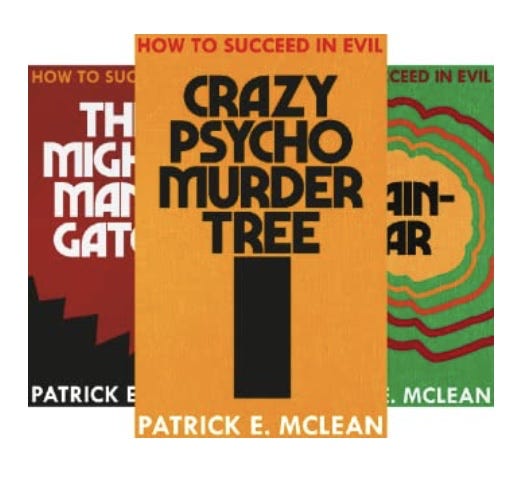

The next “How It’s Written” essay/video/podcast is going to be on Batman. And as much as I want to dig into some classic novels with How It’s Written, taking a deep dive into Batman is helping me figure out how to finish How to Succeed in Evil. If you haven’t noticed, I’ve got three books in the new series up on Amazon, Crazy Psycho Murder Tree, The Mighty Manligator and Brainitar. And if I do say so myself, the covers are growing into a nice little family.

The time is coming in the story for the character of the Lynx (Trust Fund Batman who’s not very good at it) to take more of the spotlight. And so far, he’s been pretty low-resolution. More of a punchline than a character. I don’t think this has been a problem -- after all you can’t focus on everybody at once -- but that has to change.

Going back to Batman is interesting, because I am not really a “fan” of Batman anymore. I certainly used to be. There was a time when even a bad Batman story was a good Batman story for me. Frank Miller’s Batman: the Dark Knight Return blew my mind in 1986. And still think some of the finest writing with the character can be found in the Animated Series. But it is with a far older and hopefully wiser set of eyes that I return to the Caped Crusader.

I’ve seen something of the world and the real problems it has. And the foolishness of a billionaire beating up muggers and thinking he’s making the world a better place is not something I can get past anymore. I also have trouble with Batman as an insanely overpowered character. He’s got all the resources, all the smarts -- written as omnipotent -- where’s the challenge? Where’s the change?

That’s why the only good Batman stories that are actually about Batman seem to be the retellings of his origin story and tales of his end. All of the others (some of them very, very good) are about the people around Batman, most notably the villains. So I think the secret of why this character has such staying power is to be found in the villains. And he’s also lasted, because he’s cool to film.

The other thing that I’m particularly interested in is how Batman has changed to fit the anxieties of the times. When times were good, Batman was silly. When times were dark, Batman was scary. The Batman of the 80’s was a direct product of the then popular narrative of out of control criminals evolving into ‘Superpredators’. There is a particularly chilling speech from this era about this made by our current President. But everybody was in on it. And from these fears came the mandatory minimum sentencing and the “three strikes” law, both of which have help give the U.S. the largest per capita incarcerated population on Earth.

This was the era of movies like Dirty Harry and Death Wish. To bring about justice heroes had to go farther than the cops were willing to go. The police were outgunned. So, these heroes, and Batman among them, had to do the things the cops wouldn’t. I’m not sure the logic of this holds up outside of stories, even though the late 80’s and early 90’s, by the numbers, were a more violent time than the one we live in now. (Although homicide rates are jumping in many cities.)

My point here is that the character of Batman changed to deal with the psychological experience of the audience, rather than whatever might have been the reality. And that’s sometimes a tough thing for me to remember. My impulse is to seek the ground reality of what’s going on. But, in a strange way, that’s not what matters for story.

In a somewhat frustrating discussion I recently had with a friend about COVID, I uttered these words, “It doesn’t matter what anybody thinks about the virus, the fear is real.” The reality of a situation pales in comparison to how we feel about it.

That we use fiction, drama and music to grant an emotional release from otherwise irresolvable psychological tensions is hardly a new insight. It’s what the Ancient Greeks called Catharsis.

Shawn Coyne, of storygrid.com and editor extraordinaire (he’s going to get his own episode of How It’s Written) has suggested that the thriller is THE genre of our age because it is so well-suited to relieve modern anxieties. I think that’s right, but I also think that unless something is very tightly and well-plotted, it doesn’t stand a chance in our distracted age. So six of one…

Our anxieties are different than the anxieties that forged the current iteration of Batman. Now the cops, both in fact and imagination, have vastly more power and seemingly little accountability. Batman as something of an ultra SWAT team isn’t needed anymore. I wish this was my insight, or I could remember where I came across it, but I think it was from some random person on reddit. Nevertheless, it is brilliant. And an original thing to do with Batman would be to have him take on crooked, overpowered, racist police in a violently anti-establishment story. I think this kind of storyline seems unlikely to be really pursued as long as the current iteration of Batman is making sufficient money.

This is sad, because I am all for comics exploring every possible storyline. Whenever anybody freaks out about, something replacing Tony Stark with Riri Williams or gender-swapping a character, or any other imaginative thing, I’m in. That’s what those characters and stories are for. The Avengers today are vastly different than the characters that Stan Lee created. Even though Stan created them, his versions aren’t holy. What makes comics great is this freedom and creative ferment. In terms of story, there is almost no fundamental creativity in film anymore. And I think it’s no coincidence that most of the liveliness of film (for better or worse) is coming from the faster moving and more creative medium of comics. Film’s R&D and audience building has been outsourced to other mediums.

Another question I’ve had along the way is, how desperate was D.C. when they took a chance on Frank Miller’s dramatically different take on the iconic character? If Batman, and all of comics, weren’t languishing, would they have made this move?

Of course, there are many more thoughts and far more coherence coming in the next video/essay/podcast, but all of this is by way of opening the question up to you: What do you think about Batman, and what questions would you like to see answered?

One Last Lovecraft Video

I set out to do one quick video/essay on one of Lovecraft’s short stories, thinking it would be easier to do than delving into a book. It turned into two long essays and a tip video. As Donald Westlake wrote, “Whenever something sounds easy, turns out there’s a part you didn’t hear.”But, for sake of experimenting with YouTube algorithms, I’ve condensed what I’ve learned down into six short observations. I really like how these videos are coming together and I hope you do too.

Here are my insights:

Facts that Change Meaning

Skeptical Protagonist

Informational Suspense

Description Grounding Fantasy

Powerful Images

Story Within Story

As always, thanks for your support and your feedback is always welcome. Just hit reply.