This week, I'm trying something a little different. In addition to this essay and podcast, I made a video.

It’s part of my ongoing series, “How It’s Written” I’m explaining, in detail, why I think the TV show the Mandalorian is so well-written. And to do that, I delve into the world of the internal story. I think this essay it's more fun as a video, but it totally works as a podcast or an essay. So consume in the form that you find most palatable.

Introduction

Today on "How It's Written" we're going to dig into the immensely popular Mandalorian, I've seen lots of people commenting on this story, good and bad, but I don't think any of them have really nailed what makes the show so great.

But that's not surprising, because that's what a well-crafted story does. It hides its workings so that you are drawn into and through the story, without fully realizing what's being done to you.

But I'm going to lay it all out for you. Obviously, if you haven’t seen the whole show, here’s your spoiler alert. Go binge it and come back.

The most important thing to realize is that for all it's wonderful action sequences, The Mandalorian is driven by its internal story. And if you don't know what I mean by that, or that all great stories are driven by the internal conflict, stick around.

Internal v. External Story

So, quick primer. One way to think about an internal story is that it is the story that matters most to the main character. I think this is what William Faulkner meant when he said, “The only thing worth writing about is the human heart in conflict with itself.”

Take Rocky, for example. On the outside, Rocky is a movie about a hopeless loser who tries his best who gets a shot, tries his best, and loses. In fact, he gets beat up and loses in front of his girlfriend. But on the inside, it's a triumph. And we triumph with him. Which is why we love Rocky.

Could you tell the story of Rocky without the boxing scenes? On one hand, the idea is silly. The boxing is how you show the conflict on the screen. It’s how Rocky demonstrates his passion and sacrifice. When you write a book you can put the reader directly into the mind of your character, but with film or television, you can't. So you have to have some way to symbolize what’s going on in your character’s head.

But it can be anything that’s fun to film, boxing, wrestling, bobsledding, hunting a giant shark, a chess game, performing a difficult piano concerto, lightsaber duels, or a gunfight.

So here's how the show works

Every episode has the same structure. Mando gets a job, Mando does a job. He wants someone from someone, in exchange, they give him a quest, and he completes it in exciting and unexpected action sequences.

That's it. That’s pretty much all there is to the external story. It's a formula and I love it. And, unless you're over-intellectualizing it, or trying to score clicks in pointlessly snarky YouTube commentary, you love it too. Because it’s amazingly well done.

Because as fans and viewers don't want our expectations subverted. We don't want genre conventions broken. We want all of those things honored and given back to us in a way that makes them fresh and new. We want our expectations fulfilled in a way that we don't see coming, or with such a high emotional charge we just don't care.

And I think that is one reason the Mandalorian is so refreshing. It doesn't have any pretensions to being important to the culture. They're just trying to tell an entertaining story. And that’s all that George Lucas was doing when he made the original films. And it’s not a thriller. The whole world isn’t a risk. The Galaxy is not in jeopardy. The kid is. And for me, that makes the stakes more real.

Is anything in the universe going to change if Baby Yoda gets snuffed? Probably not. But, to the Mandalorian, it would be Armageddon. And that’s the internal story. Or part of it at least.

So we’ve got sixteen chapters across two seasons. And across the loom of these episodes the internal story of the Mandalorian is woven.

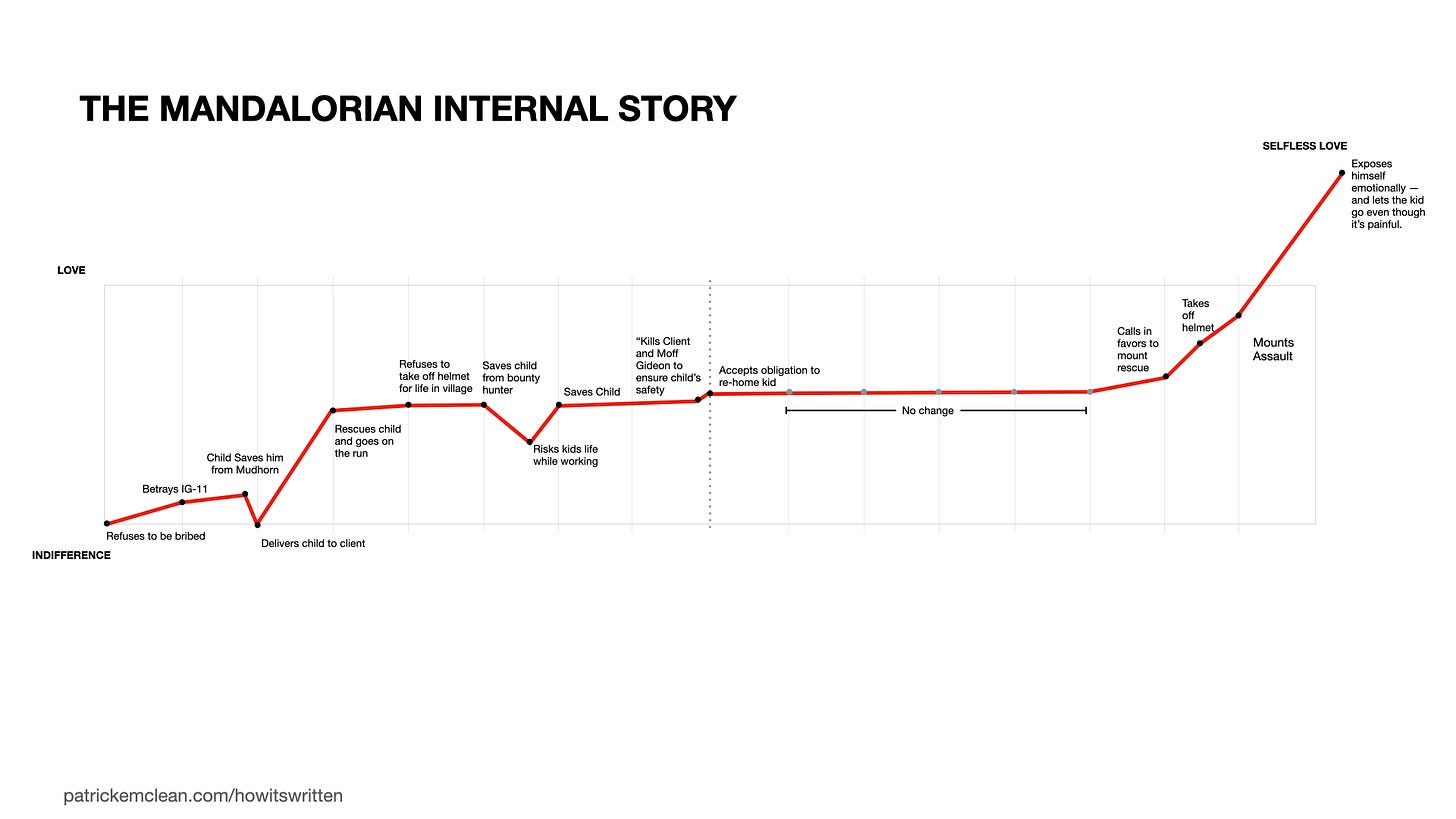

It’s the story of a traumatized orphan raised to be a violent killing machine who rediscovers his humanity by caring for an orphaned child. And his real change, I think, is from cold indifference - that detachment of the professional not just to love, but something beyond love. I call it selfless love.

I’m going to go through this in detail, but my first thought is that it is kind of a small story. It doesn’t feel like two seasons worth of television. So I think any flaws in this show are because they were shucking and jiving, filling episodes. Or what you might see as a flaw or a misstep is the writers intentionally sacrificing the external story to make the internal story stronger.

The most glaring one in my mind is in Episode 14 — titled the Tragedy, but what I think of as the Return of Boba Fett. In the standoff, Boba Fett demands that the Mandalorian takes off the jet pack. This means that he doesn’t have it on when the Child is taken by the Dark Troopers.

Honestly, this is very, very dumb. Why wouldn’t he have put his jet pack back on? Seems very valuable, not the kind of thing you’d leave lying around? Because, if he had it, he’d just fly up to save the Child either, saving him or dying in the process. And it’s very important for the internal story to have the child taken from him. Because it is in recapturing the child — because the big fight that is to come, is how he will show that he loves the child.

These “missteps” sets up a bigger, more satisfying story beats in the end.

Find me anything you love and I will find you a misstep. This show isn’t perfect. But nothing is. Work doesn't succeed because it's flawless. It succeeds because its strengths overcome its flaws. And that’s worth knowing if you want to be a maker instead of a critic.

This why hatchet job reviews and commentary bother me. Everything has flaws. And it takes no real skill or insight to them. What's harder to explain is why anything is good. In other words, how its strength’s overcome its flaws.

In the first episode, there are only two beats in the internal story. 1. Mythrol tries to bribe him to not take him in. And the Mandalorian doesn’t accept. Because, even though he’s not exactly a good guy, he’s a man with a code. Which the show will beat us over the head with for a couple of episodes.

This is the way.

This is the way.

This is the way.

Yup, he’s got a way. Because this is a Western and Samurai movie. And Westerns and Samurai movies are the same thing. Because even if you swap out the pistols for swords a showdown is a showdown is a showdown. Yojimbo is a Fistful of Dollars. The Seven Samurai is The Magnificent Seven.

And Kurosawa, the guy who made these Samurai epics, was in turn influenced by earlier Westerns. The cycles of influence never end.

Until in 1970, Kazuo Koike and Goseki Kojima produce a Japanese comic called Kozure Okami. Which literally translates as "Wolf Taking Along his Child" but which you probably know as Lone Wolf and Cub.

It’s a monster manga epic. This is the first volume and there are twelve of these books in the series. As you can see from the fabulous cover art by Frank Miller, we’ve got the cute kid in the baby carriage and everything. So it seems like it’s the same as the Mandalorian, but it’s not. Because of, you guessed it, the internal story.

Now I love Lone Wolf and Cub, so don’t take this as a real criticism, but compared to the Mandalorian, The Wolf — Ogami Itto — is kind of an asshole. Or a real hardass. At the beginning of the story, he has been ordered to commit suicide — his wife is dead and his clan has been betrayed. He is setting off on a path of revenge, but he’s got this little boy. So he lays out a sword and a ball and lets the kid choose. If the kid chooses the ball, he’s going to “send him off to be with his mother.” In other words, kill him. But the kid goes for the sword. So he takes him with him in one of the most satisfying stories of reckless child endangerment I’ve ever read.

But that’s not the Mandalorian’s story. And we don’t quite know it yet. The only hint we get in this episode is when he tells the armorer, “I was a foundling.” So when he teams up with IG-11 and the droid wants to kill him, the Mandalorian shoots him in the head.

Why? Why would a ruthless professional, one who’s code includes the phrase, “I can bring you in warm or I can bring you in cold” not let the Droid kill the kid? Well, it could be that he wants the money for himself. We’ve both seen the show, so we know it’s not. It’s that he sees himself in the kid. He was rescued by a Mandalorian in a gunfight. And we’ll get all of that in the third episode

The second episode is fun, including the line, “I’m a Mandalorian, weapons are my religion.” But from the internal story perspective, only one thing happens. The kid saves him from the Mudhorn. Now, it’s super geeky awesome that baby Yoda used the force, but for the internal story, it doesn’t really matter how the kid saves him.

In the third episode, he delivers the Child to the client and takes his Beskar to the armorer to make a new set of armor. While it’s being made, we get a flashback sequence that shows him as an orphan. A flashback sequence that for me, broke the flow of the episode a little. It was exposition I didn’t think we needed the first time I watched it. EXCEPT, I think we did need it. For the internal story. Because he’s about to blow up his entire life.

So he goes to his ship, and we have a great moment with the little metal ball. I think the technical term for this is Recognition by Token. The ball is a symbol for the kid. This is very skillful here because, in film, we can’t crack open his head and know what is going on. But if he stares at the metal ball the kid played with, what else could he possibly be thinking about?

It’s a lovely internal moment and quietly one of the biggest moments in the series. Does he leave the kid or does he rescue him? There are two things to note about this.

A crisis is always a choice.

Great crises are never a choice between good and bad things.

A crisis is always a choice between irreconcilable things. Think Sophie’s Choice.

In this moment the Mandalorian recognizes that he’s not who he thought he was. He’s not just a Mandalorian, inside, he’s still also that scared 5-year-old kid. Except this time he’s big and he’s strong and he knows how to fight. So what’s he going to do? Which one of these identities is he going to kill? Because a ruthless, cold-blooded bounty hunter doesn’t break the deal. But if he doesn’t break this deal, that little 5-year-old boy inside of him is going to die.

So he goes back, rescues the child, and goes on the run. And this is also gigantic on an external level. Because he blew up his entire external life. Now he can’t be a bounty hunter anymore. He’s on the run with the kid. And he is estranged from all the other Mandalorian. He has no idea what comes next.

Next episode, we have the wonderful defense in-depth scene against the bandits with the AT-ST. Which is a great introduction to a great character, Cara Dune. Who is a female badass, who looks like she’s a female badass. Bravo proper casting. I don’t want to get too deep into the details of the external story but I will point out that tactically, this may be the best battle scene in all of Star Wars.

This episode is also the Magnificent Seven in a nutshell. Call it the Magnificent Duo. And what’s important about this episode is he that won’t take off his helmet. He’s going to leave the child because it’s best for the child. But Bounty Hunters come and they have to stay on the run. But the very moment before that attack, Cara Dune lays this on him.

Cara Dune: (incredulous) That's it? So, you can slip off the helmet, settle down with that beautiful young widow and raise your kids sitting here sipping spotchka?

And he refuses. No taking off the helmet. This is the way. He’s a man with a code. Shane rides off into the sunset.

Now the chapter is fun action in the desert, but a bit of a nothing burger for the story that’s driving this whole thing. The stakes aren’t raised on the key value. He does what he has done before, saves the kid from the bounty hunter.

In Chapter 6, the Prisoner, the Mandalorian has taken a job with old associates. And this is a bit of reversal from love to indifference. He’s risking the child’s life Ogami Itto style. You could see it as he doesn’t have a choice, but I dunno. Seems a little sloppy and risky for a professional. But he saves the kid in the end, the status quo is maintained, and we’re off to Chapter 7.

To keep the kid safe, The Mandalorian pulls together all of his allies in a plot to kill the Client. Which is bittersweet for me. Because I love Werner Hertzog’s performance. “He is so marvelously nihilistic. As at home in the RealPolitik of the crumbling of empire as a crow feasting upon a battlefield.” Seriously, I love that guy.

Over the next two episodes, The Mandalorian kills the client and, we think, Moff Gideon but that’s kind of what he’s done before. But it can be read as just getting himself out of a mess. But tanking on the obligation to find the child’s people and see that he is taken care of, that’s a new step up.

At the end of episode seven, we have this great speech by Moff Gideon.

Moff Gideon: You have something I want. You may think you have some idea of what you are in possession of. But you do not. In a few moments it will be mine. It means more to me than you will ever know.

At the open of episode eight, we have the Scout Tropper scene. Written by Taika Wattiti — because of course it’s written by Taika Wattiti — this scene is amazing. We get utter humanity from two Storm Troopers. Funny, sympathetic, it feels like the most real scene in the whole show for me. But, we can’t like these guys too much, because they are about to get absolutely murdered by IG-11. So what does Taika have them do. Punch Baby Yoda. Now, even though you totally sympathized with them, it’s totally okay they get killed.

That’s so well done. Instantly one of my favorite scenes of all time.

Also, I have to point out that IG-11 steals the entire first season for me. It’s his episode. It’s called Redemption, is because the droid redeems himself.

The group hears the Child squeal over the comms. Cut to IG-11 on the speeder bike with the Child in a bag strapped to his chest. ]

IG-11: Kuiil has been terminated.

[ Cut to the common house. ]

Din Djarin: What did you do?

IG-11: (over comms) I am fulfilling my base function.

Din Djarin: Which is?

[ Cut to IG-11. ]

IG-11: To nurse and protect.

But, from an internal story standpoint, IG-11’s sacrifice prefigures the sacrifices that the Mandalorian will make for the Child. Because I think you have to see a person who never takes off his helmet as someone who’s trying to be a machine — and IG-11 as a machine that is trying to be human.

This is all bullshit, from the text of the story. With IG-11 insisting repeatedly, that he’s never been alive. But I think my explanation is what most people get as a viewer, if only as a feeling.

THE HELMET

Again, we get the Mandalorian refusing to take off his helmet. He’d rather die than show his face to another living thing. And, the scared little boy inside him just assumes that when he is powerless before the Droid, that IG-11 is just going to kill him. My guess is that there’s not a lot of room for weakness in the code of the Spartans.

But IG-11 is not alive, so we have a loophole.

Now, if you're not a writer, you probably don't think about story much at all. You just enjoy it. Which means, when a story is well constructed, you don't notice any of the plot points. Your emotions are running high and you just want to know what happens next. Both on an intellectual and an emotional level, you are drawn into the story.

But if a story isn't together well, you notice all the errors and the gaps in the story.

This is why, I think, if you want to understand what makes great stories, great, you have to outline them. Because, on first inspection, they've cast their spell over you and it's very difficult to see them clearly.

Since The Mandalorian won't take off his mask in the beginning, it means, he HAS to off his mask in the climax of the story. Now, if you say this out loud while watching season one for the first time with your friends, you're a jerk. But if you are Jon Favreau trying to write a television show that's what you call a clue.

Very often stories are worked back to front. What's your great ending? Now, how do you set up that great ending? Twists are easy-er. Great scenes are easy-er. But great endings are rare, so one very good school of thought is don't start writing until you have your ending.

Because just assuming a great ending will be waiting when you get there can really get you into trouble. As I think we've seen with other Star Wars stories. And, of course, Game of Thrones. *Shudder*

Anyway — IG-11 makes the Mandalorian promise to take care of the child. And we get real emotion out of the Mandalorian from this.

Din Djarin: (voice rough with emotion) No. We need you.

IG-11: There is nothing to be sad about. I have never been alive.

Din Djarin: I'm not sad.

IG-11: Yes you are. I'm a nurse droid. I've analyzed your voice. (caressing the Child in farewell)

Then we get a stupid ridiculous action sequence. This is something that you would do playing with Star Wars action figures. And part of me loves it and the other part just doesn’t care. Because, as we’ve seen from following the internal story — it doesn’t matter. It’s a boxing match. A symbol of the internal struggle and triumph.

Annnnd, season two.

For what I read as the internal story of the Mandalorian, nothing happens for like seven Chapters. Oh, plenty happens, in the way of action. And I like all of these episodes. I even like Chapter Ten with the crazy ice spiders and it’s Deus ex Machina ending. Because I’m bought into the internal story by this point. And, for that story, the jeopardy is: is Baby Yoda going to get caught eating the Frog lady’s children?

I think Blake Synder of “Save the Cat” would call these episodes “Fun and Games” it’s the promise of the premise. The Mandalorian is doing cool Mando things. He’s taking care of the kid, but it’s not like the stakes of his sacrifice are rising.

Then Moff Gideon captures the kid. And he kills a main character.

Blows up the man’s ride. But it’s more than blowing up the man’s ride. That ship is a character in the show in the same way the Millennium Falcon is. Once it’s gone, things can’t really be the same. Maybe this is an intentional signal, maybe not. But the story formula is broken. Losing the ship is a powerful sign that we’re not going back to the way things were.

The Mandalorian calls in all his allies and they put together a plan to get the kid.

But along the way, we have another climax to the internal story. He needs the location of Moff Gideon, but to get it he has to break his code and take off his helmet. Which he does. Is this it? This the big scene where the Mandalorian removes his helmet — well, not exactly. But I think it actually heightens the big scene. Because what we see is that he doesn’t exactly know how to be a person without the helmet. He’s damaged, and to protect his weak point, he has donned armor.

And what he’s armored himself against is trauma. All that terrible shit that happened to him, not only his parents being killed but also the terrible things that happened making him a Mandalorian. To the Mandalorian, foundling might just be another term for child solider. And the time-honored way — to make superhuman warriors — from Spartans to SEALS — is to put them through trials that only a very few can survive. This guy is broken and we see it in his eyes in Chapter 15

We also get the great scene where Bill Burr just blows the whole operation because he has to shoot his ex-commander. “Yeah, was it good for them though?” For me, this is the most political moment in the entire show. But it doesn’t feel forced and is totally consistent with the character; and what is the arc of most of the secondary characters in the show.

Every single one of them redeems themselves, just as the Mandalorian redeems himself in the end. Look at the transformations. Greef Carga goes from running bounty hunters to becoming a governor. The Mandalorian brings the Sandpeople and the people of Mos Pelgo together. Cara Dune goes from wanted fugitive to Marshall. Bill Burr redeems himself when he kills his commander and blows up the base.

For all the violence, this is a show about redemption.

At the end of episode fifteen, he puts Moff Gideon on notice with a lovely bit of parallelism, repeating Moff Gideon’s speech back to him word for word.

Now, this is not strategically sound, but it’s so cool, who cares? I’m not here for a lesson in tactics, I’m here to be entertained.

So, Fight, fight, fight. Rescue the kid, trapped on the bridge. Robots hammering at the door. All is lost — but then a lone X-wing flies in.

“GREAT WE’RE SAVED”

Now, I don’t want to underestimate the feels that come with Luke Skywalker making an appearance. It got me. And it really got me because the prequels and the sequels were so bad. My goal with these essays is not to be critical — and there are things to be learned from those stories. But they were bad. And, especially with the sequels, maybe the expectations, the corporate meddling, all of that made it impossible to make it good. Honestly, I thought the first one did an amazing job of threading an impossible set of needles — but after that, ugh.

And those prequels, “messa say *hurling noise*.”

Now, you may feel differently and that’s fine. I don’t blame or judge you. But what you have to understand about me is that my Dad took me to see Star Wars in 1977. I was five. And we saw it, in the theatre, at least three times.

I loved that movie so much that whenever a movie would come on television with the 20th Century Fox intro, with the drum roll and the fanfare.

I would stop whatever I was doing on the off-chance, on the hope that it might just be Star Wars.

It almost never was.

Empire Strikes Back blew my mind. Return of the Jedi wasn’t at good as that, but it was close. Luke saving and forgiving his father is still very powerful. Maybe more powerful now that I am a father and I come to understand a little bit about what having a son means. And it is saying a hell of a lot that a piece of pop culture still works on any level 38 years later. Or 44 years later if you count from the first film.

Here’s the thing, that five-year-old boy is still inside me. Honestly, I didn’t have a very happy childhood. I haven’t always had that great of a relationship with my Dad. We both can be very difficult people. It was his first time being a Dad and my first time being a kid, so neither of us knew what the hell we were doing, but I remember the moments surrounding those films as being very happy.

And since Return of the Jedi, that five-year-old kid has waited for that Star Wars to show up again. To this day, my ears still prick up when I hear the 20th Century Fox fanfare. Because maybe, just maybe it’s going to be that Star Wars movie I’ve always wanted but never got to see. But it never has.

The lesson a writer could learn from this is the expectations you set with a book, or a film or a genre are crucially important. And if you don’t handle them correctly, you’re going to be in for rough sledding.

But the five-year-old me doesn’t care about any of that. He’s been waiting for Luke Skywalker to show up on-screen since 1983.

Not this guy:

This guy:

So yeah, that was an emotional moment for me. And I don’t care about the quality of CGI. It didn’t matter anyway, because tears welled up in my eyes.

I tell you all that so you can put what I will say next into proper context. That moment was genius. But it’s not storytelling genius. It’s a manipulative, sentimental genius. And if an emotional moment like that is wrong, I don’t want to be right. For reasons beyond my conscious control, I am all in.

But, it’s still Deus ex Machina. The God from the Machine. The term was coined by Aristotle, who used it to point out that it’s generally bad writing. This kind of thing has been recognized as a mistake since 300 B.C. But in this case, it’s a mistake you want to make.

Deus Ex Machina (not a New Wave Band)

So here’s how it worked in Ancient Greece. At the end of the play they would literally use a crane to drop a totally new actor, playing a god onto the stage and he would magically resolve everything. But now, 23 centuries later, instead of a crane we get an X-wing dropping the god into the story.

But it doesn’t matter. Because all this only resolves the external story. And the internal story is what matters.

Let’s break it down.

As the Dark Troopers are banging on the door, Moff Gideon gets a hold of a blaster. And when he shoots at the child, the Mandalorian throws his body in front of the shot to save Baby Yoda. For me, this is a superfluous beat. Meh, it’s just his life. Mando has risked his life a whole bunch for the kid.

But at the very end, after Luke has cleaned house, The Mandalorian risks, far, far more.

In the end, he risks his identity.

He grows and changes to save the child. And he loves the kid so much that his ego — that wounded thing inside him that fights to hold onto his code, that won’t let him take off his helmet, that holds onto all the pain and the trauma because the Ego needs it; believes without it, he won’t exist.

That same thing in all of us that clings tightly to who we believe we are — that it gets in the way of us becoming someone better — that won’t let go even when things about us, threaten to destroy us and everyone else around us. The Mandalorian loves the kid so much, so unselfishly, that he lets him go.

He doesn’t do it to be the hero. He doesn’t do it to save the kid’s life, or his own. He does it because the child needs it from him. And he loves the child so much, he has to give it to him. Loves him enough to let him go, even though it had to hurt like hell, even though, he’s probably not going to know who the hell he is for a while. Because his ego has been dissolved in an act of selfless love.

THAT is a story. That is a character arc. That is an ENDING.

And while I could quibble over beats or choices or minor things, when you see the whole arc of what’s really going on, I don’t know why you would waste your time. It’s like complaining about a rainbow because you think it should be six inches to the left. It’s fucking rainbow jackass! If you’re not going to enjoy it, you’re not going to enjoy anything.

If you’ve liked this episode, you should totally subscribe. And if you like the way I think about story, you should probably check out my latest series, How to Succeed in Evil. Here’s a link that get you a free copy of the first book.

Thanks for watching, and I’ll see you next time.

Share this post